posted 3rd May 2023

The Value of the Returning Workforce

In this time of tech talent shortages, are businesses missing out on a crucial worker pool?

Of the population of working-age people in the UK, about 25% - that is, around 10 million people – do not currently have a job. The reasons for this are wide and varied, but roughly speaking can be divided into two groups: those who are unemployed, and those who are instead “economically inactive”.

Unemployment is officially defined as people aged 16-64 who are actively seeking a job and available to work, and they make up only around 10% of the total 10 million people who are not currently working. The remaining 90% are not currently available to work – rather, they are out of work, not seeking work and therefore not claiming unemployment benefits. Many of these people are out of work due to sickness or disability. Others have caring responsibilities which prevent them from working or are full-time students. The remainder, for the most part, are simply out of work by choice – early retirement, for the over-50s.

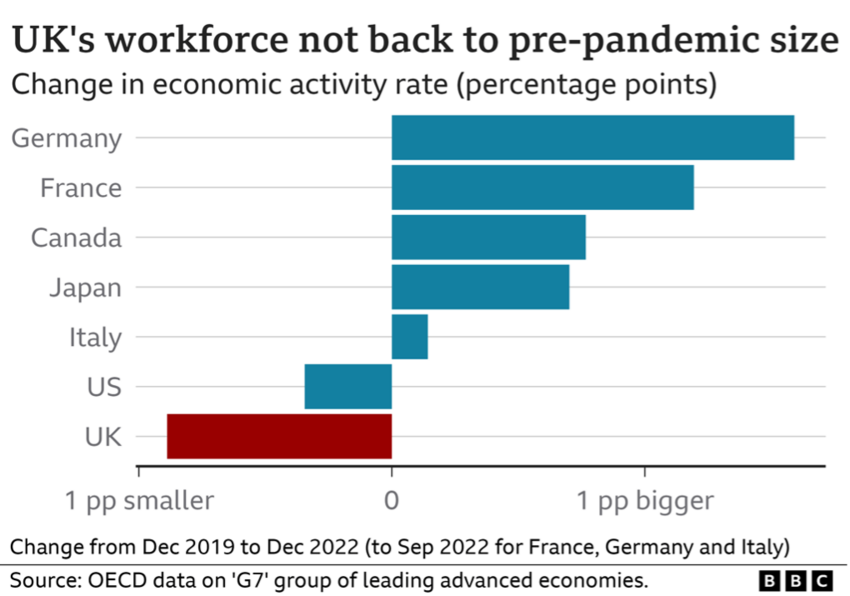

Another long-lasting effect of the COVID-19 pandemic, all major countries, the UK included, saw their workforces shrink. However, unlike most leading economies globally, the UK still has around 400,000 less people in its workforce than it did in December 2019. A report published by the House of Lords in December 2022 found that this increase in economically inactive people was down to reasons including rising levels of sickness, and a significant increase in those opting for early retirement. This number, however, is quite significantly changing.

In the second half of 2022, and in the months since, however, the UK population have continued to be impacted by yet another external force – the so-called cost of living crisis, which has made it much harder for many to survive on the same budget as they once did. This has led to a slow increase in the economically inactive returning to work. In fact, during the period of August to October 2022, the Office for National Statistics estimate that around 76,000 people in the UK stopped being economically inactive – representing a 0.2% drop in economically inactive people from the period before. This number continues to drop, as more and more people begin to return to work. This is to say nothing of those who are economically inactive but would like to be in work –it is for instance estimated that around 500,000 of those aged 50+ who are currently economically inactive would like to have a job.

Support for those returning to the workforce has historically been an area in need of greater investment and focus. All the way back in 2016, PWC published a report focused on women returning to work following a career break, claiming that “addressing the career break penalty… could boost the UK economy by £1.7 billion”. For those (predominantly female) who are returning to work after a period of caretaking responsibilities, but also the over-50s coming out of early retirement and those with disabilities, the barrier to entry can often be significant enough that it can impact their ability to even get their foot through the door with potential employers.

The tech job market in 2022 and 2023 has been particularly challenging, with notable skills shortages driving up wages and making jobs that much harder to fill. In a candidate-scarce market, new pools of talent are more valuable than ever. Hiring returners can be a much more cost-effective way to source talent. These workers do not typically place the high salary demands on employers in the same way more junior hires often do. In particular, the tech market is seeing an influx of junior workers who are both driven by and have only experienced the wage war environment that has been created in the post-pandemic, post-Brexit talent-shortage. Returning workers often have different priorities when searching for opportunities that will help them re-enter the workforce.

The challenge with tech hiring, however, is the same as the reason why tech-related jobs continue to be remarkably buoyant even amid an economic downturn: it evolves rapidly, and often encourages a level of constant adaptability and innovation. For those returning to the workforce, particularly those who have been out for several years, the lack of recent experience and up-to-date knowledge can be an insurmountable barrier to success. Providing these returning workers with support, or actively targeting them as an untapped talent pool, could be the innovative resolution to a persistent problem across much of the tech market. Understanding what drives the people within this talent pool is the first step towards successfully both attracting and retaining them.

Implementing the right softer benefits can be a huge step in the right direction. Offering flexibility on working hours, or working location, for those with caring responsibilities (such as parents), or just creating more part-time roles plays to an often-instrumental factor for those returning to work. This flexibility should also extend to reducing the stigma around issues such as parental-leave requests. Allowing parents, or those with other care responsibilities, the freedom to fulfil their care duties, not just in severe emergencies but in the smaller daily inconveniences, is an investment in the long-term wellbeing of the people who make up a workplace.

Promoting this as part of the hiring process is a great way to attract candidates who are returning following a career break. Beyond this, using positive wording in job adverts to explicitly call out to these candidates is a good way to signal that they are an important and desirable part of the applicant pool.

Offering flexibility on working hours, or working location, for those with caring responsibilities (such as parents), or just creating more part-time roles plays to an often-instrumental factor for those returning to work.

When hiring, consider also ensuring that the application and interview process also gives candidates an opportunity to speak about their experiences gained outside of the workplace (as suggested by the Business Disability Forum). This can further prevent candidates from feeling alienated, especially where they can often already feel discouraged about their odds.

The action shouldn’t stop at the hiring process, of course – it requires follow-through, and a commitment to providing support to returning workers throughout the entire course of their career at the company.

The action shouldn’t stop at the hiring process, of course – it requires follow-through, and a commitment to providing support to returning workers throughout the entire course of their career at the company. The Centre for Ageing Better, for instance, advises workplaces also commit to creating a more age-inclusive workplace culture. This includes eliminating age-bias in hiring and encouraging career development and health support for workers regardless of age.

Similarly, ACAS offers advice on where employers can start to tackle creating an inclusive workplace for disabled workers. All employers have a legal responsibility to make reasonable adjustments and protect disabled workers from discrimination. However, this should only be the beginning. It is crucial that employers and managers are able to understand what disabilities can look like (or not) and how they can affect an employee’s performance at work. This can then help in implementing solutions that allow disabled employees to succeed in their job. It’s often said that anyone can become disabled at any time – reducing the stigma and ignorance around disability will, among a wealth of many, many other benefits, inevitably awaken employers to the fact that there are many disabled people who either already have significant knowledge, skills and/or workplace experience, or are otherwise entirely capable of succeeding in their careers. The only thing missing is intelligent, empathetic, meaningful support.

Offering training programmes is also a crucial factor to supporting returning workers, particularly in the fast-paced tech job market. “Returnships” are, as defined by Women Returners, professional-level, competitively paid placement[s] for 3-6 months, with a strong possibility of an ongoing role at the end of the programme”. Essentially – internships for those who are returning to the workforce. By actively investing in growing the skills and capabilities of these workers, a company can reap the long-term benefits of both moulding the skills of its workforce and showing a great duty of care and respect towards its employees. Returnships aren’t the only format available to employers, however – just one example of way to provide a supportive period of transition to returning workers.

These programs also don’t necessarily have to be “soft” – they can be intensive, aimed at bringing a worker up to speed in as short a time as possible, whilst also ensuring that they are learning in a way that is accessible, can help build their confidence, and offers as much support as possible. Many companies have already experienced great success with these schemes – techUK, for instance, runs formal returner programmes across a number of corporate bodies in the UK. These schemes are in fact often less costly than internships, as they often focus on recruiting staff who are already qualified and experienced.

With the gender gap in IT still prevalent, however, and tech skill shortages still posing a significant problem, it is clear that not enough is yet being done. If these problems are unlikely to disappear in the near future, then perhaps it’s time to start implementing longer term solutions like returning workforce programmes at a higher rate.

The Difference Engine is a recruitment and executive search firm specialising in technology.